Cork, a bustling coastal city, serves as both a county in itself and as the vibrant capital of County Cork, residing within the charming province of Munster. It’s perched 51 miles southwest of Waterford and 126 miles in the same direction from Dublin, and is home to over 80,000 residents. Ranking as Ireland’s second largest city, Cork boasts a superb harbor, with its moniker derived from the Gaelic terms ‘Corcach’ and ‘Corcach-Bascoin’, translating to “a marshy place”. This name originated from its location along the navigable River Lee.

The city’s founding is documented in Colgan’s Life of St. Nessan, attributing the establishment of a cathedral church to St. Barr or Finbarr. This cathedral drew a significant number of disciples from all regions, transforming a once-desolate area into a bustling city. The Annals of the Four Masters claim that St. Nessan passed away in 551, suggesting that St. Finbarr might have lived earlier than the 630s, as proposed by Sir James Ware.

The original city emerged on a limestone rock near the south branch of the River Lee, expanding westward from the cathedral towards Gill Abbey. However, the island crafted by the Lee is considered the true heart of the city, with its development credited to the Danes. Despite raiding the old city for over three centuries, the Danes settled here in 1020, but their reign was short-lived, ending in defeat and destruction by fire in 1038.

The city suffered further tragedy, with a lightning strike destroying it in 1080. Despite attempts by the Danes of Dublin, Waterford, and Wicklow to retake it, they were defeated by local forces. Simultaneously, Dermot, Foirdhealchach O’Brien’s son, razed and looted the town, seizing St. Finbarr’s relics.

At the time of the English invasion, the city and its surrounding areas were held by the Danes under Dermot Mac Carthy, Prince of Cork or Desmond. Upon the arrival of King Henry II in 1173, Mac Carthy was the first to submit to his authority, surrendering the city of Cork and paying tribute for his principality. The English soon took over, but due to a lack of royal forces, they had to retreat, and Mac Carty regained control. Although several battles and sieges ensued over the years, the English eventually reclaimed the city and solidified their control by building an additional fort, keeping the men of Desmond under check. The first recorded civic magistrate, Despenser, became provost of Cork in 1199.

Fast forward to 1381, the city marked the passing of Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March and Ulster, and the lord-deputy. Thereafter, the city went through a relatively calm period until 1492 when it welcomed Perkin Warbeck, who claimed to be Richard, Duke of York. After a failed rebellion and his subsequent defeat, the city’s mayor was executed, leading to a stronger English influence in the city in the late 15th century.

During the 16th century, the city endured sieges and rebellions, but the resilience of its inhabitants never waned. Notably, Queen Elizabeth presented Maurice Roche, mayor of Cork, with a silver collar of the order of St. Simplicius in appreciation of his service against the insurgents. This symbol of valor and dedication remains preserved in the city to this day.

At the start of the major Desmond rebellion, Cork became the epicenter of English military operations, with Sir John Perrot making an appearance alongside six warships to shield the port from a potential Spanish attack. In 1598, the Vice-President of Munster, Sir Thomas Norm, was forced to hunker down in the city to avoid the uprising spearheaded by O’Neill from Ulster. In 1601, this city served as the assembly point for the army that the Lord Deputy had commissioned to drive the Spaniards out of Kinsale. An additional reinforcement of 2000 English soldiers soon joined them. Camden described the city during this period as an oval-shaped, walled city divided and surrounded by a river and having only one continuous street connected by a bridge. Although it was a small trading hub attracting significant footfall, its rebellious surroundings necessitated a constant watch, akin to a city under siege.

The Mayor and the Corporation were initially hesitant to acknowledge James’ ascension to the throne following Queen Elizabeth’s demise in 1603. The citizens armed themselves, stood guard at the city gates to deter the entry of soldiers, disarmed the Protestants, and only accepted the authority of the Mayor. They even organized defenses and attacked Shandon Castle and the Bishop’s Palace. These places of unrest were put under control when the Lord Lieutenant marched his forces into Cork on May 11, rebuilt the Queen’s Fort as a citadel to keep the city in check, and constituted the city liberties as a separate and independent county in 1608. In 1613, King James I proposed splitting Cork into two counties in a letter to Sir Arthur Chichester, but the Earl of Cork, who had loaned money to Lord President Villiers for the repair of Cork and Waterford forts, opposed the idea. In 1636, Algerines returned and with the help of the French, terrorized the coastal inhabitants.

In March 1642, General Barry and Lord Muskerry initiated a blockade on the city. The city’s garrison, however, made a successful sally, routed the insurgents, and claimed all their baggage and carriages without a single casualty. In 1644, two plots to betray the city to the insurgents were unveiled and quashed. The city populace pledged allegiance to the parliament with Cromwell’s arrival in 1649. However, in 1688, a group of Irish infantry led by Lieutenant-General Mac Carty entered the city after midnight, disarming the Protestant residents, pillaging the wealthiest homes, and spreading chaos in the nearby villages.

James II showed up shortly after, and in the fall of 1689, the governor, Lord Clare, arrested and jailed the Protestant inhabitants, with many being transferred to nearby Blarney and Macroom castles. In September 1690, William III’s forces, under the command of the Earl of Marlborough and the Duke of Wirtemberg, besieged the city. Despite an agreement with the citizens, the governor, Mac Elligott, burned the suburbs, and Shandon Castle, among other fortresses, were taken without resistance.

After a five-day siege, the city surrendered, with around 4500 soldiers taken as war prisoners, though many later escaped, and some were blown up in the Breda man-of-war docked in the harbor. During the attack, the Duke of Grafton, a volunteer in William’s army, was killed. King William and Queen Mary were proclaimed by the resumed magistrates after the royal forces took over the city on September 29.

Post-Revolution, the city’s annals have little of significant interest to record. In 1746, the Cork militia comprised 3000 infantry and 200 cavalry, along with a well-equipped company of 100 gentlemen led by Colonel H. Cavendish. In 1787, the future King, then Prince William Henry, visited the city while commanding the ship Pegasus, which was docked at Cove. Two years later, the city faced a severe flood that submerged the streets and caused massive property damage. In 1789, the first mail coach arrived in Cork from Dublin.

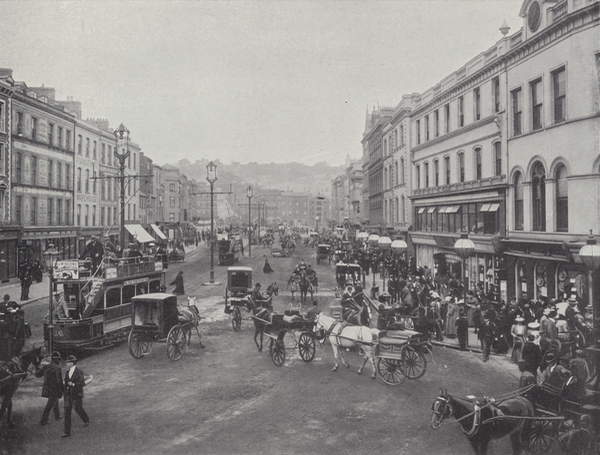

In the early 17th century, the city was largely confined to a single main street, now known as North and South Main Street. Significant expansion and improvements didn’t begin until the reign of William III when the city started to develop new streets and public buildings. By 1701, the city had only two entrances, one from the north leading from Dublin, the other from the south coming from Kinsale. There were only two wooden bridges at the time, dubbed North and South, which, according to a law passed during the reign of George I, the city corporation was allowed to rebuild in stone.

Mid-century city records and maps show that a navigable branch of the river used to flow through South Mall, rendering the area where the southern houses of that street now stand an island. Another small area called Goose Island existed beyond that, which is presently occupied by Charlotte-quay. For many years afterwards, another branch of the river flowed along Patrick Street, allowing vessels to navigate up with every tide.

The city’s growth accelerated due to its exceptional harbor, making it a key commercial hub for the region. The city was traditionally considered to include the urban center, the suburbs, and the liberties – all forming the county of the city. However, the liberties now form part of the larger County of Cork, as per a law passed during the reign of Queen Victoria.

The River Lee splits into two branches west of the cathedral, surrounding a two-mile-long, half-mile-wide tract where the ancient city was built. When the branches merge again on the east side, they form a wide estuary, marking the start of the harbor. Today’s city has grown far beyond these original boundaries, with numerous new streets having been developed north and south of the river branches.

The minor channels that used to run along the streets have been arched over by the corporation, allowing for the creation of broader streets. Nine stone bridges now span the two primary branches of the river, connecting with the district established for local taxation in 1813 under a law passed during the reign of George III. This district, which includes the tract of land between the river branches, covers an area of 2,379 statute acres.

The city has a picturesque and lively appearance, particularly with the recent widespread improvements. The main streets are broad and well-maintained, and most of the houses are large and well-constructed. Many of them have a clean, if somewhat dark, look due to their clay-slate and roofing slate construction. Some houses are built from local grey limestone, while others have cement facades. The new streets are mainly lined with red brick houses.

The city’s streets are maintained by the Commissioners of Wide Streets, a body corporate that was originally established by a law during the reign of George III. Every year, they spend approximately £6000 on maintaining, cleaning, and improving the city’s streets. The commissioners also have the power to license all types of hire vehicles and have established a set of by-laws and rates to regulate them.

The city is lit by gas, supplied by the General United Gas Company of London under a contract with the Commissioners of Wide Streets. The company, whose works are located on the river’s southern branch, provides an ample supply of gas. The city’s water supply comes from the River Lee, lifted by two large water wheels into a large reservoir and then distributed through metal pipes to the lower parts of the city. Initially, houses were provided with water for an annual fee of £2.2, but a recent application was made to Parliament to allow the company to adjust the rate based on the value of the houses.

The water works, located on the north side of Wellington Bridge, were initially built by the corporation, but were later divided into 100 shares, with 25 retained by the corporation and the rest purchased by private individuals. Prior to the establishment of a formal police system, the city had an informal security force of one officer and 80 men, housed in guardhouses in Tucky Street and Shandon.

Bridges in Cork City

Several bridges span the Lee River, many of which are modern and architecturally impressive structures. Patrick’s Bridge, the furthest bridge on the river’s northern branch navigable by vessels, was built in 1789 from a design by M. Shannahan. Originally constructed by a group of shareholders, it was a toll bridge with a portcullis until its removal by the Commissioners of Wide Streets in 1823. Comprising three elliptical arches and an open balustrade, it is entirely built from hewn limestone and connects the magnificent line of quays that run on both sides of the river through the city’s main part.

The North Bridge, which also crosses the northern branch, was built from stone early in the last century at the corporation’s expense. It replaced an old wooden bridge that, along with a similar bridge at the southern end of the main street, had long been the only way to reach the town from the countryside. Extensively renovated and widened by the corporation in 1831, it now features two cast-iron footpaths and serves as a vital link between North Main Street, the butter markets, and the populous Shandon districts.

Wellington Bridge, located at the city’s western end near the Mardyke, stands just before the Lee’s main channel splits. This impressive hewn limestone bridge, designed by Richard Griffith and built by the Pain brothers, features a central 50-foot arch and two side arches each spanning 45 feet, with solid parapets. The bridge opens a fine route to the new western road, close to George the Fourth’s Bridge, which crosses the river’s southern branch.

The latter bridge, built entirely from hewn limestone in 1820, is a plain one-arch structure. Midway between it and the Lee Mills is an attractive single-arch bridge that leads from the new western road to the county jail and house of correction via a raised causeway.

Clark’s Bridge, built by the corporation in 1726, is a red clay-slate structure that links Great George’s Street and the cathedral. The South Bridge, also built by the corporation a few years prior on the site of an ancient wooden bridge, is a neat three-arched structure constructed from hewn limestone and has been expanded with the addition of two footpaths.

Parliament Bridge is an attractive edifice built from hewn limestone with an open parapet. It connects South Mall with Sullivan’s Quay, which is accessible to considerable-sized vessels.

Anglesey Bridge, designed by Richard Griffith and built by Sir Thomas Deane in 1830, is an elegant hewn limestone structure with cast-iron parapets. It features two elliptic arches, each 44 feet in span, separated by a 32-foot waterway crossed by two parallel drawbridges. These drawbridges can be raised to allow vessels to pass upstream, and they also regulate traffic flow, ensuring that each vehicle stays on its side. Built at a cost of more than £9000 funded by the new corn-market commissioners, this bridge provides access to Black-rock, Douglas, and Passage and connects Warren’s Place and the eastern end of South Mall on the north to the new corn-market on the south side of the river.

Scenery

The city is enveloped by exceptionally beautiful landscapes, particularly to the east where two routes, the Upper and Lower Glanmire Roads, follow the northern bank of the Lee River. One is set on high ground and the other runs alongside the beach. A variety of new streets, terraces, crescents, and stand-alone villas have been built on the gentle slopes, offering breathtaking views of the Lee River, the city, Blackrock, and the fertile district encircled by the Carrigaline hills.

The southern riverbank’s scenery, stretching from Anglesey Bridge to Blackrock and Passage, is delightfully varied with a mix of elegant homes, lawns, gardens, and tree plantations that reach the water’s edge. These homes offer splendid views across the vast expanse of water to the lush hills of Rathcoony. The beautiful surroundings, pleasant climate, abundance and quality of water, fertile soil, and excellent markets have attracted many affluent families from far and wide to settle here. They have built their homes in an array of architectural styles at strategic points near the city.

The entrance from Dublin via Patrick’s Bridge is remarkably picturesque. The road meanders through the Glanmire valley before entering the Lee valley opposite Blackrock Castle, where it meets the road from Waterford, Youghal, Midleton, and Cove. It continues westwards beneath the lush plantations of Lota Beg and the fertile Kathcoony hills, dotted with villas overlooking the estuary. The approach from Limerick is via a newly laid road that winds through a beautiful, rolling landscape, crossing a charming valley via a viaduct supported by six tall arches just a short distance from Blackpool. The entrance from the west and south follows the new western road that runs parallel to the Mardyke, nestled between the Lee River’s two main branches. After crossing George the Fourth’s Bridge, it offers one of the city’s most significant improvements. The approach from Cove via Passage is through Douglas village, passing numerous beautiful cottages and entering the city by Anglesey Bridge.

The Mardyke, a mile-long, elevated promenade situated midway between the two branches of the river, is a prime spot for walks. It is lined by a double row of tall, flourishing elm trees and offers expansive and diverse views. The Botanic Garden, once a favourite place to visit, was sold in 1836 and subsequently transformed by its new owner, the Very Rev. Theobald Mathew, into a cemetery reminiscent of Père la Chaise in Paris. The graves are scattered amidst shrubs, plants, and flowers. Broad gravel paths cross the grounds and several impressive monuments stand out, including one for Murphy and O’Connor that features a life-size mourning angel sculpted from white Italian marble by John Hugan, a Cork native.

A striking equestrian statue of George II can be found at the base of the Grand Parade, near the south branch of the river. To the city’s northeast, atop a commanding hill, are the Barracks for infantry and cavalry, constructed in 1806. They house up to 156 officers, 1,994 soldiers, and 232 horses, and include a hospital for up to 140 patients. In the southern suburbs, there’s also a military hospital for about 130 patients, which serves as a strategic point during times of conflict.

The South Mall is home to the elegant County Club, a building erected in 1826 at a cost of around £4000. It includes public and private dining rooms, secretary and steward quarters, reading, billiards, and card rooms, as well as bedrooms. The club has about 300 members, each of whom pays a £5 admission fee and a yearly subscription of the same amount. Naval and military officers only pay the annual subscription. Two other clubhouses exist in the Grand Parade and at the intersection of Tucky Street and Grand Parade.

The city’s theatre, built in 1759, was a well-planned structure by acclaimed actors of the day, S. Barry and H. Woodward. However, it was destroyed by fire a few years ago and has yet to be rebuilt. It was traditionally open for a few months every year. Other social events such as balls, concerts, races, and regattas are occasionally held.

The County and City Horticultural Society, endorsed by the Duchess of Kent, released its first report in January 1835. This showed that during the initial three exhibitions, 233 prizes were distributed for the finest specimens of vegetables, fruits, flowers, and herbaceous plants. The society is substantially supported by subscriptions, and is poised to significantly improve horticulture in the district. An Agricultural Society was established in 1836.

The Library Society, located in the South Mall and established in 1790, houses a valuable collection of over 10,000 volumes spanning science, art, and general literature. A committee manages the library, meeting every other week for book selection, member admission, and general business.

The Cork Royal Institution was founded in 1803, through private subscriptions from city and county gentlemen. Its mission is to spread knowledge and facilitate the introduction of advancements in arts and manufacturing, and to teach practical applications of science through lectures. In 1807, government support led to a royal charter of incorporation and a parliamentary grant of £2000 annually. Unfortunately, the grant was withdrawn in 1830, and lectures were subsequently discontinued. The government, however, did donate the old custom-house, a large building in Nelson-place. The institution currently houses museums of natural history and mineralogy, a library with over 12,000 scientific and medical volumes, some philosophical and chemical apparatus, and a series of casts from antiques.

The Cork Scientific and Literary Society was reestablished in 1834 and currently has about 90 members and 15 paying subscribers. Members are required to produce essays for each society meeting, which are discussed at subsequent meetings. The Cuvierian Society, formed in 1835, meets in the same location and encourages friendship among individuals interested in science, literature, and the arts.

The Society of Arts was established around 1815 to promote painting and sculpture. However, due to insufficient funds, the casts donated by the king were transferred to the Royal Institution.

The Mechanics’ Institute, established in 1824, houses a library with 1500 volumes, a reading room, and two schools: one for arts and sciences, and another for design. It has 210 members and occasionally hosts lectures on scientific topics.

The School of Physic and Surgery, founded by Dr. Woodroffe in 1811, continues to thrive. It offers lectures on a variety of medical subjects during the winter half-year. Recognized by the Royal College of Surgeons in London, the Apothecaries’ Hall in Dublin, and the Army and Navy Medical Boards, this school benefits medical students in southern Ireland. Certificates from Dr. Cesar’s lectures on anatomy and Materia-medica are also recognized by these institutions.

Prior to the recent war with France, the mainstay of Cork’s trade revolved around exporting butter and beef, primarily to support the British navy, West Indies, and ports in France, Spain, and the Mediterranean. England was a major importer of hides and tallow. At that time, the neighbouring regions were primarily pasture lands and produced barely enough corn for the local population. Vast herds of cattle roamed these lands, with the quantity of beef cured for export possibly ten times greater than now. However, a push towards agriculture has since transformed significant portions of these lands into arable farms, leading to the establishment of a robust corn and flour trade.

Cork was among the first to take trade and commerce matters into its own hands by forming a ‘Committee of Merchants’, which acted as a Chamber of Commerce. It’s been an accredited representative of the trading community since 1729 and liaises with public authorities on matters related to Irish trade.

Butter trade, considered the most crucial in Munster province, involves two types of merchants. Butter merchants buy from dairy farmers or accept butter at current prices, gambling on market fluctuations. Export merchants, on the other hand, ship the butter either on order or their own account. This trade was formerly governed by local acts initiated by the Committee of Merchants. The Cork butter was favoured in all foreign markets due to the committee’s oversight. Although all restrictions have been removed following representations to parliament from other parts of Ireland, old regulations are still upheld by the merchants. The butter is brought to the same weigh-house for quality and weight checks, and each firkin is branded with these details and the inspector’s private mark.

The weigh-house can examine 4000 firkins at once, and the average annual output over the last four years was 263,765 firkins, showing a steady increase. Butter is mainly produced in Cork, Kerry, and Limerick counties, but Cork and Limerick provide the best quality in proportion to quantity. The butter from Kerry is considered more suitable for warm climates, attributed to the abundance of soft water springs and inferior soil fertility. Carriers transporting butter from distant dairy districts also distribute groceries and other consumables. This trade also employs a significant number of coopers for firkin manufacture and ‘trimming’ or preparing the butter for export, with those destined for warm climates requiring air-tight cooperage to contain the pickle.

The corn trade in Cork has grown significantly, with recent yearly averages showing exports of 72,654 barrels of wheat, 126,519 barrels of oats, and 1,749 barrels of barley. Additionally, substantial quantities of barley and oats are consumed by the city’s distilleries and breweries. A new corn market, built in 1833, has greatly increased the agricultural produce trade. Its construction, including a bridge leading to it, cost £17,460, with contributions from the government and local property owners. The quantities of agricultural produce brought to the market have been rapidly increasing, evidenced by recent figures of 83,938 barrels of wheat, 91,743 barrels of barley, 120,597 barrels of oats, and 23,483 pork carcasses weighed there.

As previously observed, the rise in crop farming naturally curtailed beef processing but significantly boosted pork production. Though reduced, the provision trade – mainly meats for the Navy and other trading ships – is still the second most important trade next to grains. Government contracts for navy provisions are still predominantly fulfilled by Cork merchants, although a significant portion of the beef often comes from Dublin.

In recent years, the curing of hams and bacon, once only done in Belfast and Waterford, has extended to Cork and Limerick due to improved pig breeding in these southern counties. However, the former extensive trade of supplying plantation stores for West Indies proprietors has significantly diminished.

Similarly, the shipments of provisions to the West Indies are declining, barely offsetting the costs of the enterprise. The provisions trade has further suffered due to the opening of Newfoundland’s supply to foreign trade, reducing exports of pork, flour, oatmeal, butter, bacon, candles, leather, boots, shoes, and other commodities, which were returned in fish and oil.

In recent years, steam-powered navigation has boosted the export of flour to London, Bristol, and Liverpool, with an average of 79,119 sacks exported per year. This new form of transport also significantly enhanced the trade in livestock, poultry, eggs, and river fisheries products. Approximately 1,200 pigs and half a million eggs are shipped weekly, and salmon from rivers across the region, including remote parts of Kerry, is sent to Cork for export after curing.

Trade with the Mediterranean primarily involves importing goods like bark, valonia, shumac, brimstone, sweet oil, liquorice, raisins, currants, other fruits, marble, and various small articles. Wine importation is still substantial, albeit less than before due to the increased consumption of locally distilled spirits.

Salt importation from St. Ubes ranges from 5,000 to 6,000 tons annually, not including the substantial quantities brought from Liverpool. Trade with St. Petersburgh, Riga, Archangel, and occasionally Odessa, involves primarily tallow, hemp, flax, linseed, iron, hides, bristles, and isinglass but is not very substantial.

Timber from Canada is still being imported in large quantities. Despite the decline in outward West Indies trade and the ease of obtaining supplies from English ports via steamers, raw sugar imports remain consistent. However, herring imports, once a big trade, have now become almost exclusively for local consumption.

The direct foreign trade of the port has significantly diminished since the advent of steam navigation, impacting wholesale traders. Retailers, who previously relied on large stocks, can now ensure a weekly supply by steam from Liverpool or Bristol, which has impacted the value of large warehouses used for merchandise storage.

Despite the changes brought about by steam navigation, the tonnage of sailing vessels belonging to the port has significantly increased over the last 35 years. A noticeable advancement has been observed in their construction quality, and they’re now recognised for their excellence. Most of these sailing vessels are employed in Canadian timber and Welsh coal trades. The coal trade is substantial, previously supporting the Foundling Hospital through a local duty levied on all coal brought into the port.

In 1836, the port registered a total of 302 vessels, with an overall capacity of 21,514 tons and employing 1,684 personnel. This figure also includes ships from Kinsale and Youghal, now registered as hailing from Cork. By 1844, the count of sailing vessels less than 50 tons was 158, with a total capacity of 3,790 tons. Larger sailing vessels (50 tons or more) numbered 208, with a total capacity of 32,551 tons. There were 13 steamers, with a total tonnage of 2,538.

Two shipyards exist, each with patent-slips capable of accommodating 500-ton vessels for repairs. Ships of up to 400 tons are constructed in these yards. At Passage, there are also two shipyards, one boasting an impressive dry dock. These establishments collectively employ around 200 people.

During 1836, 164 British and 27 foreign ships (with a total tonnage of 29,124 and 2,912 tons respectively) engaged in foreign trade entered the port. A total of 69 British and 20 foreign ships (collectively 10,098 tons) exited. For trade with Great Britain, 2,246 vessels of 226,318 tons entered, while 1,384 vessels of 166,516 tons left the port. Interactions with other Irish ports involved 406 vessels (18,564 tons) entering and 596 vessels (20,384 tons) leaving. The annual customs duties for the year were £216,446.1, and the excise duties were £252,452.14.

In 1844, trade with British colonies involved 91 vessels of 21,129 tons entering and the same number and tonnage exiting. Foreign trade involved 74 British and Irish vessels and 17 foreign vessels (totalling 9,315 tons and 1,807 tons, respectively) entering, with 17 British and Irish and 13 foreign vessels (4,190 tons and 1,055 tons, respectively) exiting. Coastwise trade that year saw 2,390 sailing vessels and 238 steamers (a total of 252,019 tons) entering, while 1,652 sailing vessels and 280 steamers (a total of 191,343 tons) exited.

The total value of exports for a recent year amounted to £2,909,846, including goods like corn, livestock, provisions, linens, whisky, and more. Imports for the same year were valued at £2,751,684, including goods like coal, iron, textiles, haberdashery, and others.

The introduction of steam navigation has had a significant impact on the port’s trade, driving the export of agricultural produce and the import of various goods. The completion of the Great Western railway from Bristol to London has further facilitated the trade by speeding up the delivery of Irish produce to London.

Back in 1821, two steamboats were launched by a Scottish company to operate between Cork and Bristol, but they proved unfit for purpose after six months due to their high water draught. A company named St. George’s later introduced packet boats between Cork and Liverpool, and Cork and Bristol, which still run to this day and have taken over much of the port’s cargo trade. This company, with a capital of £300,000 shared among shareholders (a third of whom are based in Cork), operates seven vessels of about 500 tons and 250 horsepower each. These ships operate routes to Bristol, Liverpool, London, Dublin, and Glasgow, transporting passengers, goods, and livestock.

Additionally, there is a fortnightly steamer service to Dublin and Glasgow, owned by another company, and four smaller steamboats operate daily between Cork and Cove.

Cork Harbour

The renowned Cork Harbour, which birthed the city’s motto, “Statio bene fida carinis,” is brilliantly equipped for any extensive commercial activities. Thanks to its strategic location, robust safety measures, and top-tier anchorage facilities, it has historically served as a haven for vast fleets during times of war, supplying the British navy with superior provisions. Numerous small crafts, fishing boats, and barges, along with the area’s hardy population, have fortified Cork’s reputation among British policymakers as a pivotal point in the empire. During wartime, significant public funds were poured into supplies, infrastructure, and various other endeavours, propelling Cork’s commercial prosperity to unprecedented heights.

The primary harbour area lies nine miles beneath the city, opposite the town of Cove, where ships of any size can safely anchor. The best anchorage for larger vessels is near the now-disused Cove Fort, which functions as a naval hospital. Ships with heavy drafts can sail upriver as far as Passage, close to the city, for loading and unloading. Lighter vessels can directly reach the town quays. On the eastern side of the harbour entrance stands Roche’s Tower lighthouse, guiding ships with its powerful lamps.

Cove used to host Ireland’s only naval depot and provisioning yard during the war and remained the post-war station for a considerable fleet under an admiral’s command. Currently, an admiral is again stationed here after a period of absence. Haw bowline Island is home to sizeable naval warehouses, tanks, and other facilities. Powerful batteries sit on Spike Island, guarding the harbour entrance, and Rocky Island holds a gunpowder depot.

The Harbour Commission Board, established by the George IV act, was responsible for harbour improvements and regulating pilots. The board’s significant works include the construction of a line of quays along both sides of the river, extending around the eastern end of Lapp’s Island. Notably, they deepened the river bed to accommodate larger vessels and marked the channel’s boundaries with buoys for navigation safety.

Cork’s transport infrastructure has come a long way since the first mail coach arrived in the city from Dublin on July 8, 1789. Presently, there are day and night mails from Dublin, and mails from other places. However, these arrangements are expected to change significantly with the introduction of several Railways.

As for manufacturing, the primary trade in Cork is the tanning of leather, a thriving sector since the standardisation of duties. In a recent year, approximately 110,000 hides were tanned annually, turning Cork from a leather importer into a leading exporter. Other significant industries include corn milling, brewing, and distilling, all of which have seen considerable growth since the increase in corn production during the recent continental war.

The city is home to seven iron foundries, employing over 300 workers. There are also five factories producing tools like spades and shovels. In addition, two steel mills and a large coppersmiths’ establishment primarily serving the distilling and brewing industries can be found here. The city imports over 6,000 tons of iron yearly and around 1,000 people are engaged in various roles within the iron industry, including blacksmithing.

Numerous paper mills are scattered throughout the city, with their products being in high demand. Over 400 workers are employed in these mills. The city also boasts two sizable glass factories, specializing in flint-glass production for both domestic and international markets. Each of these factories also includes extensive facilities for glass cutting, engraving and more, and collectively employ 246 individuals.

The city’s wool-cloth manufacturing history dates back to before 1732. The primary manufacturers were the Lane family, who for over twenty years after the Union provided the entire uniform for the Irish army. Their mills, located at Riverstown, are now utilized for different purposes. At Glanmire, there are large mills for fine cloth production, and at Blarney, mills for spinning yarn to supply a cloth and camlet factory in Cork. Several wool-combing, dyeing establishments, and mills at Douglas and Glanmire where linens and cottons are finished, are also present. Rope production, particularly patent cordage, is carried out in several dedicated factories.

Many of the city’s lower-income residents find work in weaving coarse cotton-check fabrics, sold inexpensively by Todd and Co., who run a large retail establishment, similar to those found in London and Dublin. The city also produces high-quality cutlery, priced higher than similar products from England. A robust glove-making industry employs a large number of people, with locally made gloves marketed as Limerick gloves. Additionally, the city is known for the production of acids, mineral waters, and superior quality vinegar.

The canvas industry, once thriving, is now dwindling due to cheaper imports from cities like Liverpool, Glasgow, Greenock, and East Cocker. Similarly, the soap industry has shrunk due to increased farming and reduced cattle slaughtering, which has also impacted the local candle manufacturing industry, previously a primary supplier to the West Indian market.

The Bank of Ireland and the Provincial Bank opened branches around 1825, offering financial support to the local industries. A branch of the National Bank followed in 1835. The local savings bank, established in 1817, saw deposits exceeding £420,000 by the end of 1845, with a total of 34,000 depositors recorded from its establishment until the end of 1836.

The main market days are Wednesday and Saturday, but all markets are open daily. Fairs are held under city charter on Trinity-Monday and October 1st, in an open area called Fair-field, located northwest of the town. The city market, established in 1788, offers meat, fish, poultry, fresh butter, vegetables, and fruit. It’s located near the city centre with entrances from Patrick-street, Prince’s-street, and the Grand Parade, and comprises multiple detached buildings. The cattle market is held near the Shandon markets. The average annual number of cattle sold here has decreased in recent years, while the average number of live pigs sold to provision merchants remains steady at around 90,000 annually.

The city’s administrative body, or corporation, has an extensive and storied past, likely originating through customary practice rather than a specific decree. The first known formal acknowledgement of the corporation’s existence came via a charter given by John, Earl of Morton, while serving as the viceroy of Ireland under Henry II. This charter confirmed the rights of the city’s citizens over the land on which the city stands, and granted them certain freedoms and customs, modeled after those of Bristol in England. Unfortunately, the original charter no longer exists, but a copy can be found among the Harleian Manuscripts in the British Museum.

Subsequent charters have been granted throughout the years, each adding to the privileges and jurisdiction of the corporation. For example, a charter from the 26th year of Henry III’s reign provided the city and its surrounding areas with numerous rights and personal freedoms for its citizens, and instituted the role of “provost” as the chief officer of the corporation. Additional charters from Edward I and Edward II further expanded the power of the corporation and introduced the role of mayor.

Later, Edward IV’s charter granted the mayor and citizens jurisdiction over the city, suburbs, and the entire port, from the shores of Rewrawne in the west, to the shores of Benowdran in the east. Edward IV’s charter also waived any arrears on the annual rent payment of 80 marks for the city, due to the difficulties faced by the city in collecting it due to local disruptions. This charter also specified that instead of the 80 marks, the corporation would now owe an annual payment of 20 pounds of wax.

Several more confirmatory charters were granted by subsequent monarchs, with Henry VIII granting the mayor the privilege of having a sword carried before him in ceremonial events, and giving him control over the castle. Elizabeth I made the mayor, recorder, and bailiffs, as well as the four senior aldermen, peacekeepers of the city, both on land and water.

A significant shift occurred with a charter in the 6th year of James I’s reign, which designated Cork as a free city and changed the corporation’s official name to the “Mayor, Sheriffs, and Commonalty.” This charter also established the city, along with a surrounding area designated by commissioners, as a distinct county. This charter also exempted the corporation from their annual wax payment, and allowed them to hold two fairs and established a staple corporation with privileges equivalent to those of London or Dublin.

Charles I, in the 7th year of his reign, provided a charter that further clarified the governance of the city, and specified the roles and responsibilities of the mayor, aldermen, and other officials. George II later authorized two additional fairs to be held annually within the city’s liberties.

The corporation was historically comprised of the mayor, sheriffs, aldermen, burgesses, and freemen. A set of by-laws was passed in 1721 to regulate the elections of these officers and to ensure the efficient governance of the corporation.

Prior to the enactment of the 3rd and 4th Victoria, cap. 108, which regulates Municipal Corporations, the mayor was selected on the first Monday in July. The election was, in theory, by the majority of the freemen, and from a pool of resident burgesses or individuals who had previously served as sheriffs. However, the “Friendly Club,” an association of around 500 freemen, had significant sway over the elections, almost nullifying the freemen’s right to choose the mayor.

Elections for sheriffs occurred simultaneously with those for the mayor. The aldermen, who were unlimited in number, were individuals who had previously served as mayors. Additionally, there was a “common council” composed of the mayor, recorder, two sheriffs, and aldermen, capped at 24 members. If they fell short of this number, additional members were elected from among the burgesses.

The “Friendly Club” had significant influence over these processes as well. All by-laws and orders for payments and the management of corporate property originated from the common council, then later confirmed in a court of d’oyer hundred.

Apart from the recorder, the corporation had numerous auxiliary officers, including a town-clerk, a chamberlain, a water bailiff, two sergeants-at-mace, weighmasters, coroners, among others. The freemen largely elected these officers.

The appointment of the mayor, sheriffs, recorder, and town-clerk required the approval of the Lord-Lieutenant and Privy Council. The first-born sons of freemen inherited their fathers’ status, which could also be earned through a seven-year apprenticeship to a freeman or granted by the common council.

Following the recent act, the city is now divided into eight wards. The corporation consists of 16 aldermen and 48 councilors. The mayor, elected from the aldermen and councilors every December 1st, assumes office on January 1st. Both the aldermen and councilors are chosen from among the burgesses. The qualifications for these positions include the possession of £1000 above debt or a house worth £25 annually. In contrast, a burgess must own or rent a house or land worth at least £10 annually above all rates and taxes and have resided there for at least six months prior to the election.

The sheriff, recorder, treasurer, town-clerk, clerk of the peace, coroner, and other officers are still in place. The city began sending members to the Irish parliament in 1374. However, there were earlier instances of representatives serving in London. The freemen of the city had the right to vote until 1832.

The 2nd of William IV., cap. 88, retained the city’s privilege of sending two representatives to the Imperial parliament due to its significance. However, the act limited voting rights to the £10 householders and the £20 and £10 leaseholders for 14 and 20 years, respectively.

Under the old regime, the mayor, recorder, and all aldermen were justices of the peace for the county of the city, and the mayor held multiple other roles. Currently, a special commission of justices of peace exists for the borough. The constabulary police force includes one sub-inspector, two head-constables, 17 constables, and 84 sub-constables.

The municipal courts, at the time of the Municipal act’s passage, included the mayor and sheriffs’ court, the courts of city-sessions and conscience, and the police-office or magistrates’ court. Now, these courts still exist but are subject to new arrangements. The corporation’s revenue was approximately £6237 annually before the act, but increased to £7968 in 1844.

The city is incorporated within the Monster judicial circuit: both the assizes for the county at large and the county of the city take place here. Additionally, in September, the assistant barrister conducts his courts for the East Riding. The current town hall, or Guildhall, is located on the south side of the old Exchange, and houses a council chamber on the first floor where the mayor and council convene for business proceedings.

The Exchange, positioned at the intersection of Castle-street and North Main-street, is a compact, uniform stone structure, constructed by Twiss Jones in 1709 using corporation funds. However, it has been recently demolished due to its decrepit condition. The old county courthouse, previously known as “the King’s Castle,” was replaced in 1835 by a larger, more functional County and City Courthouse designed by the Pain architects. The grand building features Grecian architectural style, including an imposing portico with eight columns supporting an entablature, cornice, and pediment topped by figures symbolizing Justice, Law, and Mercy. Its interior includes two semi-circular courts and various offices designed for public and staff access without interference. The courthouse, built at approximately £20,000, stands as a testament to the architects’ taste and discernment.

The former Mansion-house, now serving as a Roman Catholic seminary, is a striking edifice erected in 1767 by the acclaimed Ducart at a cost of £3793. The entrance hall and staircase are expansive. It used to house a well-sculpted bust of George IV and a marble effigy of the first Right Hon. William Pitt in his robes of office. The large dining and drawing rooms were lavishly furnished, with a full-length figure of William III in the former. The entrance hall also contained historical artifacts including the city’s ancient “nail” or “nail head”, the old standard brass-yard, and a unique depiction of the city arms cut in stone, unearthed during the demolition of the old custom-house.

The City Gaol is a castle-like building, perched on a hill near Sunday’s-Well. Initially designed with separate sections for male and female prisoners, it now comprises 32 wards: eight for male debtors, one for female debtors, and separate wards for male and female offenders, with the remaining six serving as hospital wards. The prison offers a total of 54 cells, providing space for 162 male and 96 female inmates. Each ward comes with a day-room and an outdoor area, and one yard features a treadmill for pumping water for the prison’s supply. The facility also accommodates separate worship areas for Protestants and Roman Catholics. The City Bridewell functions as a temporary holding area for detainees pending examination or those arrested for disorderly conduct overnight.

The Gaol and House of Correction for the County are located a short distance from the city, on the south side of the new western road. The prison, originally accessed from the south, has been modified to allow entrance from the north side, achieved by constructing a bridge over the south channel and a raised walkway across the adjacent meadows. An entrance portico, modelled after the Temple of Bacchus in Athens, faces the bridge along the esplanade. The prison has undergone several expansions, resulting in a comfortable facility managed by a governor and deputy-governor, divided into various wards for different categories of inmates. The gaol, along with the surrounding grounds, are maintained in top-notch condition.

The House of Correction, built by the Pain architects adjacent to the gaol, is a well-organized structure, with a central portion and several radiating wings. It houses the governor’s quarters, separate chapels for Protestants and Roman Catholics, and an infirmary. There are 78 cells and related facilities, and a day-work room with attached airing-yards. The prison, managed by a governor, is organized for prisoner reform, with inmates employed in making their own clothing and other necessities. A tread-mill supplies water to both the prison facilities.

A decade ago, the grand jury granted £1600 for a hospital for prisoners, which extends 100 feet in front and includes a two-story central portion and wings. It houses six wards, equally divided for male and female patients.

The Women’s Prison, alternatively known as the Convict Depot, resides in the location of the ancient fortress built in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, located in the southern outskirts of the city. This prison has the capacity to hold 250 women, who are brought here from all corners of Ireland and stay until transportation vessels arrive to take them to their assigned penal colonies. While in residence, they are kept busy with tasks such as needlework, laundry and knitting, activities that not only occupy their time but also provide clothing for themselves and for all convicts transported from Ireland. Every year, approximately 1000 suits are produced this way. Educational programs have been implemented in all Cork prisons.

The establishment of the Cork bishopric is commonly attributed to Saint Barr or Finbarr, during the early part of the 7th century. His holy relics, once encased in a silver shrine, were stolen from the cathedral in 1089 by Dermot, son of Turlough O’Brian, during his looting of Cork. It is believed that Saint Nessan succeeded Saint Finbarr. In 1292, Bishop Robert Mac Donagh was twice penalised £130 for improperly conducting legal proceedings in church courts over matters under the jurisdiction of the crown. Of these fines, £84. 14. 2. was waived. In 1324, Edward II sent Philip of Slane, Bishop of Cork, as an ambassador to the Pope. His successful diplomacy led to his appointment as a member of the privy council of Ireland. Upon his return, an assembly of bishops, nobles and others convened, resolving that all who disturb public peace shall be excommunicated. The assembly also decided that small and impoverished bishoprics, which were led by the Irish, should be integrated with larger bishoprics. Additionally, it was agreed that Irish abbots and priors should accept Englishmen into lay brotherhoods, mirroring the practices in England. In 1430, Pope Martin V consolidated the vacant bishoprics of Cork and Cloyne and assigned Jordan, the chancellor of Limerick, as the bishop of the newly united diocese.

The final Roman Catholic bishop prior to the Reformation was John Fitz-Edmund from the prestigious Geraldine family, who was appointed by the Pope in 1499. After his passing, his influential family members seized revenues from Cloyne and portions of those from Cork. In 1536, Dominic Tirrey, seen as sympathetic to the Reformation, was appointed bishop by Henry VIII. He held this position for 20 years, during which the Pope appointed two clerics to the united diocese, neither of whom assumed the role. Matthew Sheyn, a strong opponent to the veneration of idols and appointed bishop by Queen Elizabeth in 1572, publicly burned the statue of Saint Dominic at the High Cross of Cork in October 1578, much to the city inhabitants’ dismay.

William Lyon, ordained as Bishop of Ross in 1582, was granted the bishoprics of Cork and Cloyne by Elizabeth in 1586. In a return to a royal visitation circa 1613, he reported that he had increased the worth of the bishoprics of Cork and Ross from £70 to £200 per annum. He also built a mansion in Ross, which was destroyed by rebel O’Donovan just three years later. In addition, he constructed an episcopal house in Cork at a cost of at least £1000. He mentioned that he never had possession of the house associated with the bishopric of Cloyne, as it was being withheld by Sir John Fitz-Edmund Fitz-Gerald and, after his death, by his heir.

Following the death of Bishop Lyon, his position was sequentially taken by John and Richard Boyle, both of whom were related to the Earls of Cork. Richard Boyle, who later became the Archbishop of Tuam, passed away in Cork in 1644. He was laid to rest in a tomb he had prepared in the cathedral during his term. During his tenure, he is credited with repairing many dilapidated churches and consecrating more new ones than any other bishop of his era. Bishop Boyle was succeeded by Dr. Chappel, who was the provost of Trinity College in Dublin. His successor was Michael Boyle, who was the son of Dr. Chappel’s predecessor. Michael Boyle was succeeded by Dr. Synge, who left several legacies to the poor in his will dated May 23, 1677.

After Dr. Synge’s death, the Bishopric of Cloyne was separate from the combined bishopric of Cork and Ross until 1835. Dr. Hetenhall, the first Bishop of Cork and Ross, experienced numerous injustices from 1688 to the settlement under King William. He personally financed the repair of the Bishop’s palace in Cork. In 1709, Dr. Brown, Provost of Trinity College, was promoted to the bishopric, a position he held until his death in 1735.

The diocese of Cork is one of sixteen that make up the ecclesiastical province of Dublin. It is entirely within the county of Cork, spans roughly 74 miles long by 16 miles wide, and has an estimated area of 356,300 acres. The chapter comprises a dean, precentor, chancellor, treasurer, archdeacon, and the twelve prebendaries.

Under the Roman Catholic church structure, Cork is its own bishopric, composed of 35 parochial districts that include 81 chapels. The total clergy, including the bishop, number 74, comprised of 35 parish priests and 39 coadjutors or curates. The bishop, who lives in Cork, oversees the union of Shandon, also known as the North Parish.

The once COUNTY OR THE CITY was a vibrant rural area renowned for its beautiful landscapes and fertile lands, nourished by several small streams and bisected by the majestic river Lee and its grand estuary. Its northern border was shared with the Fermoy barony, east with Barrymore, south with Kerricurriby, and west with Muskerry. The area encompassed the parishes of St. Finbarr, Christ-Church (or the Holy Trinity), St. Peter, St. Mary Shandon, St. Anne Shandon, St. Paul, and St. Nicholas, the majority of which were located in the city and its suburbs, excluding part of St. Finbarr’s. Parishes outside the city and suburbs included Curricuppane, Carrigrobanemore, Kilcully, Rathcoony, and sections of Killannlly (or Killingly), Carrigaline, Dunbullogue (or Carrignavar), Bollinaboy, Inniskenny, Kilnaglory, Whitechurch, and Templemichael. The district spanned over 44,463 acres, 2396 of which were occupied by the city and its suburbs. The 1835 grand jury presentments for new roads, bridges, and other infrastructure amounted to £611. 19. 7., road and bridge repairs cost £2641. 14., public buildings, charities, salaries, and other expenses were £14.592. 1. 1., police establishment cost £1148. 14.3., repayment of advances by the government amounted to £1254. 19. 6., and £8800 was allocated to the Wide-Street Commissioners for lighting and paving, resulting in a total of £29,049. 8. 5. The contemporary county of the city, or borough, under the 3 and 4 Victoria act, c. 108, incorporated the parishes of Christ-Church, St. Paul, St. Peter, and sections of St. Anne Shandon, St. Finbarr, St. Mary Shandon, and St. Nicholas. This entire region covered 2263 acres, not including 420 acres of tideway. The grand jury presentments for 1844 totaled £31,791.

The ST. FINBARR parish was a rectory, associated with the dean and chapter, and the Ecclesiastical Commissioners of Ireland. The tithe rent-charge was £742. 10. annually, with £517. 10. making up the majority of the cathedral’s economy fund under the dean and chapter’s management, and £225 were designated to the vicars-choral, now controlled by the commissioners. A resident preacher with a £100 stipend, a reader with a £75 stipend paid by the vicars-choral from their estates, and a curate, who also acted as a librarian, with a fixed stipend of £21 from the economy fund were appointed for standard ecclesiastical duties. The Cathedral of Cork, dedicated to the eponymous saint, was rebuilt between 1725 and 1735. Its reconstruction cost was covered by a duty of It. per ton levied on all coal and culm imported into Cork for five years, starting from May 1st, 1736. It received a new roof in 1817, costing £617, sourced from the economy fund. The new edifice features a Doric order, except the tower, thought to be part of the original building erected by Gilla-Aeda O’Mugin in the 12th century. It boasts a lofty octagonal spire made of hewn stone, which is positioned above the main entrance. The south houses the chapter hall, where the consistorial court is held, and the north hosts the vestry room. The choir is illuminated by a beautiful Venetian window; the bishop’s throne, made from black Irish oak, and the prebendal stalls are elegantly finished and neatly arranged. A striking white marble monument dedicated to Chief Baron Tracton, who is buried in the cathedral, was recently moved from St. Nicholas’ church to a prominent position inside the cathedral. Near the cathedral stands the Bishop’s Palace, constructed between 1772 and 1789 during Dr. Mann’s prelacy. It’s a large, well-built structure on the southern bank of the river Lee, encircled by gardens and showcasing some exquisite paintings, including a portrait of Dr. Lyon. A traditional story about Lyon’s promotion to the see, although not substantiated by official records, alleges that he was promised a promotion by Queen Elizabeth due to his heroic actions as a ship captain in numerous battles with the Spaniards. Despite opposition due to his previous profession, he was appointed to the bishopric of Cork based on his faith in the royal promise. The south of the cathedral is home to Dean’s Court, a modern house where the dean resides. A chapel of ease to this parish has also been built, as detailed in the Blackrock article. The parish of Christ-Church is a vicarage under the patronage of the Bishop. The suspended rectory, which was part of the prebend of the same name in the cathedral church and a gift from the Crown, was governed by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. Its income comes from Blackrock lands, averaging £396. 18. per annum in rent and renewal fines. The vicarage’s endowment is about £650 per annum, stemming solely from houses assessed to minister’s money. It has neither a glebe nor a glebe-house. The old church was demolished in 1716 and rebuilt in 1720 using a 1s. per ton tax on imported coal for 15 years. The steeple, which deviated from the perpendicular by 3 feet, was reduced to the roof level and finally removed completely before the church was rebuilt by the Messrs. Pain. The new structure is 97 feet by 57: its paneled ceiling rests on ranges of Ionic pillars of Scagliola marble extended across the eastern end; along the northern and southern walls are galleries supported by Doric pilasters. Several of the lower columns, along with parts of the floor, were replaced with cast-iron pillars in 1831 by Richard Beamish, Esq., a civil engineer, after being destroyed by dry-rot, effectively securing the entire edifice’s stability. Some 16th-century gravestones bearing emblematic devices were unearthed during the alterations. St. Peter’s parish is a rectory, perpetually united with the entire rectories of Nohoval, Kilmonogue, Dunbullogue, and Dunisky, collectively forming the union and corps of the archdeaconry under the Bishop’s patronage. The archdeacon’s net income is approximately £700, coming from the minister’s money assessed on St. Peter’s parish, from the tithes of the four rural parishes, and from reserved rents of houses. He compensates a perpetual and four stipendiary curates. The church, one of the city’s oldest, previously had a detached tower to the west, which once defended the city wall. Its site is now an almshouse. A beautiful tower and spire, 150 feet high, were recently erected by the archdeacon. The altar is embellished with fluted Corinthian pilasters, and on its south side was a monument, In the churchyard is a pyramid, erected over a family vault by Counsellor Hely. The living of St. Anne Shandon is a vicarage, united, by act of council in 1789, with the vicarage of St. Mary, Shandon, forming the union of St. Anne, in the patronage of the Bishop. The united parishes constitute the corps of the chancellorship, the net income of which, is about £500, arising from the minister’s money assessed on the two parishes and lands at Douglas, near the city. The church, which is the most elevated in Cork, and situated on the summit of a steep eminence overlooking the city, was built in 1722, in lieu of the old one, which had become ruinous. It is a square edifice, with a tower rising from the centre of the roof, and finished with an octagonal spire: the former contains two tiers of windows, and the latter is ornamented with a series of diminishing arches; on the apex of the spire is a gilt weathercock, 11 feet in length. This spire is the highest in the city, and forms a conspicuous landmark from the sea. The church contains several handsome monuments, among which is a well-executed one of white marble, to the memory of the Rev. Dr. Mann, late bishop of the diocese. The living of St. Mary, Shandon, is a vicarage, in the diocese of Cork, united from time immemorial with the vicarage of St. Anne, Shandon, forming the union of St. Anne, in the patronage of the Bishop. The church is a neat and commodious building, with a small spire. The living of St. Paul’s is a vicarage, united by act of council in 1789, with the vicarage of St. Nicholas, forming the union of St. Paul, in the patronage of the Bishop. The united parishes constitute the corps of the treasurership of the cathedral church. The old church having become ruinous, a new one was erected in 1836, at an expense of £3000, raised by subscription, aided by a grant of £1500 from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. The church is a handsome structure in the later English style, with a square embattled tower, surmounted by a slender spire rising to the height of 154 feet from the ground; the interior is well arranged, and has a beautiful window of stained glass in the east end. The living of St. Nicholas is a vicarage, united by act of council in 1789, with the vicarage of St. Paul, forming the union of St. Paul, in the patronage of the Bishop. The united parishes constitute the corps of the treasurership of the cathedral church. The old church, situated in the street bearing the name of the parish, was taken down in 1834, and a new one erected in its stead, in the lower road, by the Rev. R. Beamish, then incumbent, at an expense of £1800, defrayed by subscription and a grant from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. It is a neat building in the later English style, with a square embattled tower surmounted by a pinnacle at each angle, and in the centre a slender spire rising to the height of 120 feet from the ground; the interior is well arranged, and has a beautiful stained-glass window in the east end. The minister’s income is about £600 per annum, arising from minister’s money, tithes of lands, and a rent-charge on a plot of land at Lota. The county of the city, or borough, is co-extensive with the union of St. Finbarr and the parishes of Christ-Church and St. Nicholas, and those portions of the parishes of St. Mary and St. Anne which are within the limits of the borough.

The religious administration of St. Mary’s Shandon is both a rectory and vicarage, and it’s integrated with the rectory of St. Catharine, near Shandon. The administration has been historically connected and it’s supervised alternately by the Duke of Leinster and the Reverend Robert Longfield. There is no church-owned land or clergy residence here. The tithe, which is a religious tax, is £18. 15, while the clergyman’s income is £100, in addition to a £95. 10 rental from 7 houses located on Shandon-street. This income is subjected to an annual payment of £75 to a licensed assistant minister. The church that used to serve the ancient parish of Shandon, encompassing the modern-day parishes of St. Mary, St. Anne, and a portion of St. Paul, used to be where St. Anne’s church is now. This old church suffered damages from various conflicts due to its location near Shandon Castle, and it was ultimately destroyed by Irish forces around 1690. A new, tidy church was constructed in 1696 on a different site, and the Ecclesiastical Commissioners recently provided £198. 19 for its restoration.

St. Anne’s Shandon is a rectory, also under the alternating administration of the Duke of Leinster and the Reverend Robert Longfield. Like St. Mary’s, it lacks church-owned land and a clergy residence. Its religious tax is £180, and the clergyman’s annual income is around £370. The church is a large, attractive structure, featuring a 120-feet high tower that was built from donations in 1772, on the site of the old Shandon church. Because it was constructed on an elevation, it’s easily visible from most parts of the city. The Ecclesiastical Commissioners recently contributed £259. 9 for its refurbishment. St. Luke’s chapel, a subsidiary chapel to this parish, was constructed in 1836 near the Brickfields. It exhibits the later English architectural style, designed by the Pain architectural firm. The chapel features a western tower topped with a light, graceful spire and two tall pinnacles at the eastern end. The building also includes spacious classrooms located below floor level at the eastern end, where the land slopes steeply downwards. The late Board of First Fruits provided £1000 for its construction, matched by the same amount from public donations.

St. Paul’s is a rectory, under the alternating administration of the Duke of Leinster and the Reverend Robert Longfield. The parish was established in 1726 from the districts of the East Marsh in the parish of St. Mary Shandon, and Dunscombe’s Marsh in that of Christ-Church. The income, around £200 annually, comes solely from assessments of the clergyman’s income, and there is neither church-owned land nor a clergy residence. The church is a tidy structure in the Grecian style, funded by public donations at the time of the parish’s establishment, and it stands on land granted by the city corporation.

St. Nicholas is a rectory, merged in 1752 with the rectories of St. Bridget, St. John of Jerusalem, St. Stephen, St. Mary de Narde, St. Dominic, and St. Magdalene. Collectively, they make up the chancellorship, supervised by the Bishop. The income for the union, prior to the passing of the Rent-charge act, was £293. 18., arising from houses assessed for clergyman’s income, the tithes of St. Magdalene amounting to £21, the tithes of St. Nicholas, and houses producing £5. 18. per annum. The church, previously a subsidiary chapel to St. Finbarr’s, was constructed in 1723 from donations by Bishop Brown and others. It’s a small, tidy structure located in the southern part of the city. A free church has recently been finished near the South Infirmary. The church of St. Brandon, once located on the north side of the river, on the road to Youghal, has been completely destroyed, but its cemetery remains in use.

The principal SCHOOLS in connexion with the Established Church arc the following. St. Stephen’s Blue-Coat Hospital was founded pursuant to a grant of lands and tenements in the North and South liberties by the Honourable William Worth, by deed dated Sept. 2nd, 1699, now producing a rental of £443, which, with the interest of £500 saved by the trustees, is expended in the maintenance, clothing, and education of 22 boys, the sons of reduced Protestant citizens, and in aid of the support of four students at Trinity College, Dublin. The premises are situated on an eminence in the parish of St. Nicholas, and comprise a good schoolroom, dining-hall, apartments for the governor, and suitable offices, with an enclosed playground in front. The Green-Coat Hospital, in the churchyard of St. Anne’s Shandon, was founded about 1715, chiefly through the exertions of some military gentlemen and others to the number of 25, who by an act passed in 1717 were incorporated trustees, for the instruction of 20 children of each sex in the rudiments of useful knowledge and the principles of the Protestant religion, and for apprenticing them at a proper age, with a preference to the children of military men who had served their country. No regular system appears to have been introduced prior to 1751, but subsequently 40 children were clothed and educated till 1812, the number has since been increased by aid of a parliamentary grant. The income amounts to £176. 14. per annum, of which £164. 2. arise from donations and bequests, and the remainder from annual subscriptions: the chief benefactors were, Daniel Thresher, who devised the lands of Rickenhead, in the county of Dublin, formerly let for £26 per annum on lease, which expired in 1844, when the lease was renewed at a rent of £106. 6. per annum; and Francis Edwards, of London, who devised eleven ploughlands in the parish of Ballyvourney, let permanently for £11 per annum. A librarian and treasurer, chosen from among the trustees, act gratuitously. The building consists of a centre and two wings, the former containing two schoolrooms and also apartments for the master, in the west wing are a library and board-room, with apartments for the mistress, and the other wing contains lodging-rooms for about 38 poor parishioners.

Deane’s Charity Schools were founded under the will, dated in 1726, of Moses Deane, Esq., a Protestant of this city, who devised the rents of certain premises held for a term of years in trust to the corporation, to accumulate until they should yield a sum of £1200 for the parishes of St. Peter, St. Nicholas, St. Mary Shandon, and Christ-Church, respectively. The four sums were to be invested in land in the county of Cork, and the rents applied to the instruction and clothing of 20 boys and 20 girls of each parish. The portion of the bequest assigned to the parish of St. Peter having been paid, the school was re-opened in 1817, and now affords instruction to 30 boys and 35 girls, of whom 20 of each sex are clothed: the endowment produces £55 per annum, and an additional sum of about £50 is raised annually by subscriptions and the proceeds of an annual sermon. This forms the parochial school of St. Peter’s. The

portion assigned to the parish of St. Nicholas was obtained by the Ven. Archdeacon Austin, and was afterwards vested in the hands of the Commissioners for Charitable Bequests by the Rev. Dr. Quarry. In 1822 a grant was procured, and a plain and commodious building containing two schoolrooms was erected in Cove-street, to which, in 1831, the Rev. J. N. Lombard, the late rector, added a schoolroom for infants: the funds amount to £189. 14. per annum. The portion belonging to St. Mary’s Shandon was lost for many years, but by the exertions of Dr. Quarry, the late rector, £800 were recovered, which sura, by a legacy of £100 and accumulated interest, has been augmented to £2000 three and a half per cent, reduced annuities. A commodious building of red brick, ornamented with hewn limestone, and containing apartments for the roaster and three spacious schoolrooms, with a covered playground for the children, was erected in 1833 under the superintendence of Dr. Quarry, at the cost of £743, collected by him for that purpose. An infants’ school affords instruction to 100 children; and a Sunday and an adult school are also held in the building. The boys’ and girls’ schools are supported by a portion of the dividends arising from the funded property, by local subscriptions, and a collection after a charity sermon; and the infants’ school, by a portion of the same dividends and subscriptions. The parish of Christ-Church obtained no portion of Deane’s bequest, the lease of the premises from which it was payable having expired. The Diocesan Schools for the sees of Cork, Ross, and Cloyne, are held respectively in Cork, Rosscarbery, and Mallow. On the eastern side of the cathedral is a free school founded by Archdeacon Pomtroy for the instruction in reading, writing, and arithmetic, of ten boys, to be nominated by the bishop: the master’s original salary of £10 having been augmented by the dean and chapter, and by a bequest by the late Mrs. Shearman, to £30, twenty boys are now instructed gratuitously and are also taught the mathematics. Attached to the school is a library, founded by the archdeacon, and much enlarged by a bequest of Bishop Stopford’s: it contains more than 4000 volumes, chiefly valuable editions of the classics and of works on divinity, and is open gratuitously to the clergy of the diocese and the parishioners of St. Finbarr’s.

According to the Roman Catholic Divisions, the city with the suburbs is divided into three unions or parishes, St. Mary’s and St. Anne’s, St. Peter’s and St. Paul’s, and St. Finbarr’s. St. Mary’s and St. Anne’s union comprises nearly the whole of the Protestant parishes of St. Mary, St. Anne, and St. Catherine: the duties are performed by the bishop, six curates, and two chaplains. The parochial chapel, which is also the cathedral, is a spacious structure, with a plain exterior: the eastern end, having been destroyed by an accidental fire, was rebuilt, and, with the rest of the interior, decorated by the Messrs. Pain in the later English style of architecture; the altar-piece is extremely rich, and similar to that of the abbey of St. Alban’s, in England. There are chapels of ease at Brickfields and Clogheen. The former, dedicated to St. Patrick, is a handsome edifice in the Grecian style by the Messrs. Pain: the principal front is ornamented by a lofty and elegant portico of eight columns of grey marble, and approached by a flight of steps, extending along the entire front from the centre of the roof rises a cupola, supported by eight Corinthian columns, surmounted by figures representing as many of the Apostles; the whole crowned by a pedestal and cross. This chapel was opened for divine service, October 18th, 1836. St, Peter’s and Paul’s, comprising the Protestant parishes of the same name, with portions of those of Christ-Church, St. Anne, and St. Finbarr, is a mensal of the bishop: the duties are performed by an administrator and two curates. The parochial chapel, a plain edifice, built in 1786, has an elegant altar in the Corinthian style, with a fine painting of the Crucifixion. St. Finbarr’s comprises the Protestant parish of St. Nicholas, most part of St. Finbarr’s, and a small portion of that of Christ-Church: the duties are performed by a parish priest and four curates, one of whom resides near Black rock, and officiates at the chapel of ease there, which is noticed in the article descriptive of that village. The parochial chapel is in Dunbar-street, a spacious building, erected in 1776, in form of a T: under the altar is the figure of a “Dead Christ,” of a single block of white marble, executed at Rome, at an expense of £500, by Hogan, a native of Cork. In the chapel is also a monument to the memory of the Rev. Dr. M’Carthy, coadjutor bishop, who is represented in the act of administering the sacrament to a person labouring under malignant fever, thus expressing in the liveliest manner the cause of his death.