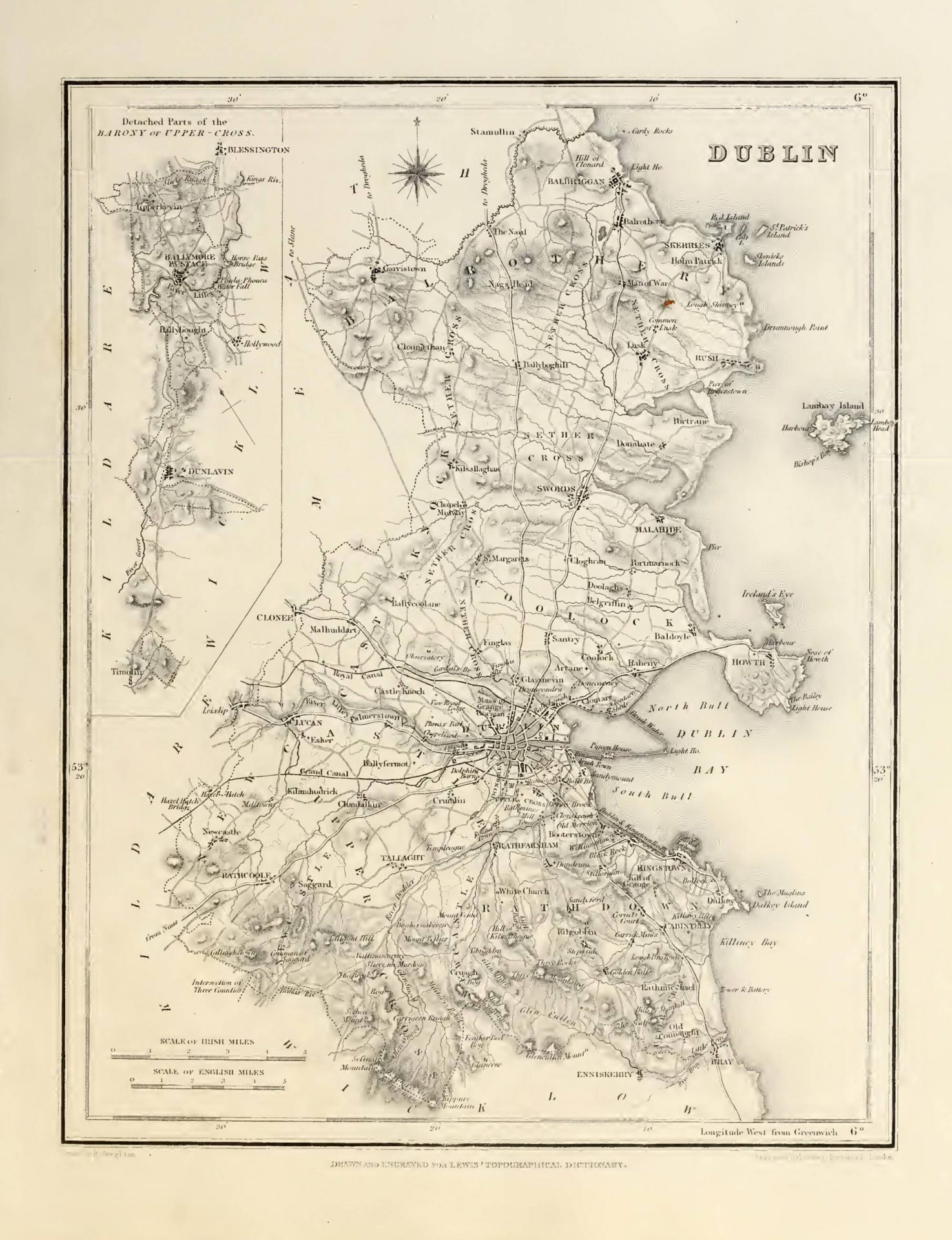

DUBLIN (County of), a maritime county of the province of Leinster, bounded on the east by the Irish Sea, on the north and west by the county of Meath, on the west and southwest by that of Kildare, and on the south by that of Wicklow. It extends from 53° 10′ to 53° 37′ (N. lat.), and from 6° 4′ to 6° 36′ (W. Ion.); and comprises an area of 226,414 statute acres, of which 196,063 are arable land, 19,312 uncultivated, 5519 plantations, and 5520 in the city and towns and villages. The population of the county, in 1821, exclusively of the metropolis, was 150,011; in 1831, 183,042; and in 1841, only 140,047, owing to its reduced limits, conformably with a late act of parliament.

The earliest inhabitants of this tract of whom we have any authentic notice were, a native people designated by Ptolemy Blanii or Eblani, who occupied also the territory forming the present county of Meath, and whose capital city was Eblana, presumed on good authority to have been on the site of the present city of Dublin. By some writers it is stated, that in subsequent remote ages, the part of the county lying south and east of the river Liffey constituted part of the principality of Croigh Cuolan; while that to the north was included in the principality of Midhe, or Meath. The Eblani, whatever may have been their origin, probably enjoyed peaceable possession of the soil down to the commencement of the Danish ravages, and the seizure and occupation of Dublin by these fierce invaders. At this era, the tract now described experienced its full share of calamities, until the celebrated battle of Clontarf, which terminated in the overthrow of the military power of the Ostmen in Ireland. But that this people had made extensive settlements within its limits, which they were subsequently allowed to retain as peaceable subjects of the native Irish rulers, is proved by the fact that, at the period of the English invasion, a considerable part of the county to the north of the Liffey was wholly in their possession, and from this circumstance was designated by the Irish Fingall, a name signifying either the “white foreigners” or “a progeny of foreigners;” the word “fine” importing, in one sense, a tribe or family. The country to the south of Dublin is stated, but only on traditional authority, to have been called at the same period Dubhgall, denoting the territory of the “black foreigners,” from its occupation by another body of Danes. Though all Fingall was granted by Henry II. to Hugh de Lacy, Lord of Meath, yet the number of other proprietors, together with the circumstance of its being the centre of the English power in Ireland, prevented the county, which was one of those erected by King John in 1210, from being placed under palatine or another peculiar jurisdiction. Dublin originally comprised the territories of the O’Birnes and O’Tooles in the south, which were separated from it, and formed into the county of Wicklow, so lately as the year 1603. At an early period, the jurisdiction of the sheriff of Dublin appears even to have extended in other directions far beyond its present limits; for, by an ordinance of parliament, about the close of the 13th century, preserved in the Black Book of Christ Church, Dublin, was restricted from extending, as previously, into the counties of Meath and Kildare, and into some parts even of the province of Ulster.

The county is in the diocese and ecclesiastical province of Dublin, and, for purposes of CIVIL jurisdiction, is divided into the baronies of Balrothery, East and West. Castleknock, Coolock, Nethercross, Newcastle, Rathdown, Uppercross, and Dublin, exclusively of the county of the city. The irregularities of form in the baronies were until recently very great: that of Newcastle was composed of two portions, that of Nether-cross of six, and that of Upper-cross of five, three of which, constituting the parishes of Ballymore-Eustace, Ballybought, and Tipperkevin, on the confines of Wicklow and Kildare, were wholly detached from the rest of the county. The irregularities of the two latter baronies were owing to their constituent parts having been dispersed church lands, enjoying separate jurisdictions and privileges, but ultimately formed into baronies for the convenience of the civil authority. The county contains the ancient disfranchised boroughs and corporate towns of Swords and Newcastle; the sea-port, fishing, and post towns of Howth, Kingstown, Balbriggan, and Malahide; the fishing towns of Rush, Skerries, and Baldoyle; the inland post-towns of Cabinteely, Lucan, Rathcoole, and Tallaght; and the town of Rathfarnham; besides numerous large villages, in some degree suburban to the metropolis, and the chief of which, exclusively of Sandymount, Booters-town, Blackrock, Donnybrook, Dolphinsbarn, Irishtown, Rathmines, and Ringsend, which were included in the late county of the city, are those of Finglas, Golden-Ball, Dalkey, Drumcondra, Stillorgan, Raheny, Dundrum, Round town, Ranelagh, Artaine, Clontarf, Castleknock, Chapelizod, Glasnevin, Donabate, Portrane, Garristown, Belgriffin, St. Doulongh’s, Killiney, Bullock. Lusk, Newcastle, Saggard, Balrothery, Little Bray, Clondalkin, Coolock, Crumlin, Golden-Bridge, Island-Bridge, Kilmainham, Milltown, Merrion, Phibsborough, Sandford, and Williamstown.

Prior to the Union, the county, exclusively of the city, sent six members to the Irish parliament, namely, two knights of the shire, and two representatives for each of the boroughs of Swords and Newcastle; but since that period its representatives in the imperial parliament have been limited to two members for the county at large: the election takes place at Kilmainham. The constituency qualified to vote in 1843, was 3307, of whom 1128 were £50, 387 £20, and 548 £10, freeholders; 549 £20, and 582 £10, leaseholders; and 113 rent-chargers. A court of assize and general gaol delivery is held every six weeks, at the court-house in Green-street, Dublin; and at Kilmainham, where the county gaol and court-house are situated, are held the chief quarter sessions, at which a chairman, who exercises the same powers as the assistant barrister in other counties, presides with the magistrates. The local government is vested in a lieutenant, 23 deputy-lieutenants, and 123 magistrates, with the usual county officers. The number of constabulary police stations is 39, and the force consists of a county inspector, 5 sub-inspectors, 6 head-constables, 37 constables, and 187 sub-constables, with 8 horses; the expense of maintaining which, in 1842, was £10,604, defrayed equally by grand jury presentments and by government. The Meath Hospital, which is also the County of Dublin Infirmary, is situated on the south side of the city, and is supported by grand jury presentments, by subscriptions and donations, and by an annual parliamentary grant, there are 35 dispensaries. In military arrangements, this county is the head of Dublin district, the chief of all the districts throughout Ireland, which are Athlone, Belfast, Cork, Dublin, and Limerick: the department of the commander-in-chief and his staff is at Kilmainham. The county contains various military stations, besides those within the jurisdiction of the metropolis; viz., the Richmond infantry barrack near Golden-Bridge on the Grand Canal, Island-Bridge artillery station, the Portobello cavalry barrack, the Phoenix Park magazine and infantry barrack, and the recruiting depot at Beggars-Bush; affording in the whole accommodation for 161 officers, 3282 men, and 772 horses. There are, besides, 26 Martello towers and nine batteries on the coast, capable of containing 684 men; and at Kilmainham stands the Royal Military Hospital, for disabled and superannuated soldiers, similar to that of Chelsea, near London. Within the county are twelve coast-guard stations, one of which is in the district of Kingstown, and the rest in that of Swords; with a force consisting of 12 officers and 96 men.

The county stretches in length from north to south, and presents a sea-coast of about thirty miles, while its breadth in some places does not exceed seven. Except in the picturesque irregularities of its coast, and the grand and beautiful boundary which the mountains on its southern confines form to the vale below, it possesses less natural diversity of SCENERY than many other parts of the island; but it is superior to all in artificial decoration; and the banks of the Liffey to Leixlip present scenery of the most rich and interesting description. The grandeur of the features of the adjacent country, indeed, gives the environs of the metropolis a character as striking as is presented by the environs, perhaps of any city in the west of Europe. The mountains which occupy the southern border of the county, are the northern extremities of the group forming the entire county of Wicklow: the principal summits within its confines are, the Three Rock Mountain and Garry-castle, at the eastern extremity of the chain, the former of which has an elevation of 1586 feet, and the latter of 1869; Montpelier hill; the group formed by Kippure, Seefinane, Seechon, and Seefin mountains, the first being 2587 feet high, and Seechon 2150; and the Tallaght and Rathcoole hills, which succeed each other north-westward from Seechon, and beyond the latter of which, in the same direction, is a lower range, composed of the Windmill, Athgoe, Lyons, and Rusty hills. From Rathcoole hill a long range diverges south-westward, and enters the eastern confines of Kildare county, near Blessington. In the mountains adjoining Montpelier and Kilmashogue are bogs, covering three-or four-square miles, but the most prominent features of these elevations are the great natural ravines that open into them southward, and of which the most extraordinary is the Scalp, through which the road from Dublin to the romantic scenes of Powerscourt passes into the county of Wicklow. From their summits, also, are obtained very magnificent views of the city and bay, and of the fertile and highly improved plains of which nearly all the rest of the county is composed, and which form part of the great level tract that includes the counties of Kildare and Meath. The coast from the boldly projecting promontory of Bray Head, with its serrated summit, to the Killiney hills, is indented into the beautiful bay of Killiney. Dalkey Island, separated from the above-named hills by a narrow channel, is the southern limit of Dublin bay, the most northern point of which is the Bailey of Howth, where is a lighthouse. The coast of the bay, with the exception of these two extreme points, is low and shelving, but is backed by a beautiful and highly cultivated country terminating eastward with the city: much of the interior of the bay consists of banks of sand, uncovered at low water. About a mile to the north of Howth is Ireland’s Eye, and still farther north, off the peninsula of Portrane, rises Lambay Island; both described under their own heads. Between Howth and Portrane the coast is flat, and partly mashy; but hence northward it presents a varied succession of rock and strand: off Holmpatrick lie the scattered rocky islets of St. Patrick, Count, Shenex, and Rockahill.

The SOIL is generally shallow, being chiefly indebted to the manures from the metropolis for its high state of improvement. It is commonly argillaceous, though almost everywhere containing an admixture of gravel, which may generally be found in abundance within a small depth of the surface, and by tillage is frequently turned up, to the great improvement of the land. The substratum is usually a cold retentive clay, which keeps the surface in an unprofitable state, unless draining and other methods of improvement have been adopted. Rather more than one-half of the improvable surface is under tillage, chiefly in the northern and western parts, most remote from the metropolis: in the districts to the south of the Liffey, and within a few miles from its northern bank, the land is principally occupied by villas, gardens, nurseries, dairy-farms, and for the pasturage of horses. Considerable improvement has taken place in the system of agriculture by the introduction of green crops and improved drainage, and by the extension of tillage up the mountains. The pasture lands, in consequence of drainage and manure, produce a great variety of good natural grasses, and commonly afford from four to five tons of hay per acre, and sometimes six. The salt-marshes which occur along the coast from Howth northward are good; and the pastures near the sea-side are of a tolerably fattening quality, but inland they become poorer. The only dairies are those for the supply of Dublin with milk and butter; which, however, are of great extent and number. The principal manures are lime and limestone-gravel, the latter of which is a species of limestone and marl mixed, of a very fertilising quality, and found in inexhaustible quantities. Strong blue and brown marl are found in different parts, and there are likewise beds of white marl, the blue kind is preferred, as producing a more durable effect: manures from Dublin, coal-ashes, and shelly sand found on the coast, are also used. The implements of husbandry are of the common kind, except on the farms of noblemen and gentlemen of fortune. The breed of cattle has been much improved by the introduction of the most valuable English breeds, which have nearly superseded the native stock. The county is not well wooded, with the exception of plantations in the Phoenix Park and the private grounds of the gentry: there are various nurseries for the supply of plants. The waste lands occupy nearly 20,000 statute acres; the largest tract is that of the mountains on the southern confines, extending about fifteen miles in length and several in breadth. The scarcity of fuel, from the want of turf nearer home, which can be had only from the mountains in the south and the distant commons of Balrothery and Garristown on the north, is greatly diminished by the ample supplies brought by both canals, and by the importation of English coal.

The county presents several interesting features in its GEOLOGICAL relations. Its southern part, from Blackrock, Kingstown, and Dalkey, forms the northern extremity of the great granitic range which extends through Wicklow and part of Carlow. The granite tract is bordered by a range of incumbent mica-slate, which extends eastwards from Shankill and the Scalp to the hills of Killiney, and which on the western side commences near Rathfarnham, passes to the south of Montpelier hill, and occupies the upper part of the hollow that separates Seefinane mountain, on the east, from Seechon on the west: in this hollow are displayed some curious intermixtures of the strata of mica-slate, granite, and quartz. In the descent from Seechon mountain, both south-westward and north-westward, towards Rathcoole, the mica-slate passes into clay-slate, containing frequent beds of greenstone, greenstone slate, and greenstone porphyry, and occasionally, likewise, of quartz. The Tallaght hills consist of clay-slate, greenstone, and green-stone porphyry, interstratified; the last rocks more particularly abounding in the eastern quarter. Rathcoole hills, and the range extending from them south-westward, are composed of clay-slate, clay-slate conglomerate, and grey wake-slate, alternating with each other. The low group west of Rathcoole is composed of clay-slate, greywacke, greywacke-slate, and granite, the last of which is found remarkably disposed in subordinate beds in the prevailing greywacke-slate of Windmill hill, whence some of them may be traced westward to near Rusty hill. This county contains the only strata of transition rocks known to exist in the eastern part of Ireland: they appear in detached portions along the coast from Portrane Head, by Loughshinny, Skerries, and Balbriggan, to the Delvan stream, the northern limit of the county.

The rest of the county, comprising nearly the whole of its surface, is based on flotz limestone, commonly of a blueish-grey colour, often tinged with black, which colour in some places entirely prevails, especially where the limestone is interstratified with slate-clay, calp, or swine-stone, or where it abounds in lydian stone. The black limestone in the latter case is a hard compact rock, sometimes of a silicious nature, requiring much fuel for its conversion into lime. Calp, or “black-quarry stone,” which is generally of a blackish-grey colour and dull fracture, and may be considered as an intimate mixture of limestone and slate-clay, forms the common building-stone of Dublin. it is quarried to a great extent at Crumlin and Rathgar. Besides carbonate of lime, it includes considerable quantities of silex and alumina, traces of the oxides of iron and manganese, and a small proportion of carbon, which gives to it its dark colour: by exposure to the air, it undergoes a gradual decomposition. The elevated peninsula of Howth consists of irregular alternations of clay-slate add quartz-rock, both pure and intermixed; on its southern coast the strata present some extraordinary contortions. The only metallic ore at present found in considerable quantity is lead, once abundantly raised near the commons of Kilmainham, and at Killiney; a productive vein on Shankill is now being worked by the Mining Company of Ireland. White lead is found in small quantities; the ore is smelted and refined at Ballycorus, in the immediate vicinity of the mine. At Loughshinny is a copper-mine, and at Clontarf a lead-mine, both now abandoned. On the south-western side of Howth, grey ore of manganese and brown iron-stone have been obtained in considerable quantities; and a variety of earthy black cobalt ore has been found there. Coal is supposed to exist near the northern side of the county, and unsuccessful trials have been made for it near Lucan. Among the smaller minerals may be enumerated schorl or tourmaline and garnet, frequently found in the granite; and beryl, a variety of emerald, which occurs in several places: spodumene, which is in great request from its containing eight per cent, of a newly discovered alkali, called lithia, is procured at Killiney, as is also a mineral closely resembling spodumene, designated killinite by Dr. Taylor, its discoverer, from its locality. The lime-stone strata usually abound with petrifactions, specimens of which, remarkable for their perfection and variety, may be obtained at St. Doulough’s, and at Feltrim, about seven miles north-east of Dublin. The shores of the county, particularly from Loughlinstown to Bray, abound with pebbles of all colours, often beautifully variegated, which bear a polish, and are applied to a variety of ornamental uses.

The manufactures are various, but of inferior importance. The most extensive is that of woollen cloth, carried on chiefly in the vicinity of Dublin: the manufacture of paper is carried on in different parts, more particularly at Rockbrook and Templeogue; and there are also cotton-works, bleach and dye works, and iron-works, besides minor establishments, all noticed in their respective localities. The banks of the numerous small streams by which the county is watered, present divers advantageous sites for the erection of manufactories of every kind within a convenient distance of the metropolis. The great extent of sea-coast affords facilities for obtaining an abundant supply of fish. Nearly 90 wherries, of which the greater number belong to Skerries and Rush, and the others to Howth, Baldoyle, Malahide, Balbriggan, and Ringsend, are employed in this occupation: there are also about twenty smacks, and five seine nets, occupied in the salmon fishery between Dublin and Kingstown; the former in the season, being likewise engaged in the herring fishery: and at Kings-town and Bullock are a number of yawls, employed in catching whiting, pollock, and herring. On the river Liffey, from Island-Bridge to the lighthouse at Pool beg, there is a considerable salmon-fishery. The harbours are mere fishing ports, except that of Dublin, and its dependencies Howth and Kingstown, upon the improvement of both of which vast sums have been expended.

The chief river is the Anna Liffey (“the water of Liffey”), which has its principal source at Sally gap, in the Wicklow mountains, and, taking a circuit west-ward through Kildare county, enters that of Dublin near Leixlip, where it is joined by the Rye water from Kildare; thence it pursues a winding eastern course nearly across the middle of the county, descending through a deep and rich glen by Lucan and Chapelizod. Below the latter, it flows through some pleasing scenes on the borders of Phoenix Park; at Island-Bridge it meets the tide, and a little below, it enters the city, to the east of which it discharges its waters into the bay of Dublin. The river is navigable for vessels of 300 tons up to Carlisle-bridge, the nearest to the sea; for small craft that can pass the arches, up to Island-Bridge; and for small boats, beyond Chapelizod: so circuitous is its course, that although the distance from its source to its mouth, in a direct line, is only ten miles, yet, following its banks, it is no less than forty. Numerous streams, which supply water to many mills, descend into the Liffey; the principal is the Dodder, the Brittas or Cammock, and the Tolka. The Dodder has its source near Castlekelly, in the valley of Glenasmuil, parish of Tallaght, and running north and east, passes by Templeoge and Rathfarnham on to Ringsend, and at the mouth of the Liffey meets the tide-water of Dublin bay. The Tolka rises in the northern part of the county, and, passing through Finglas and Glasnevin, falls into the river or bay a little below Ballybough-bridge. A stream called the Devan forms the northern boundary of the county, at Naul. Two great lines of inland navigation commence in Dublin city; but as they run in parallel directions within a few miles of each other during some parts of their course, the benefits anticipated from them have not been realised to the utmost extent. The Grand Canal was originally begun in the year 1755, by the corporation for promoting inland navigation in Ireland: in 1772, a subscription was opened; and the subscribers were incorporated under the name of the Company of Undertakers of the Grand Canal, and by the completion of this work connected the capital both with the Shannon and the Barrow. It is navigable for 164 miles, being 99 from Dublin to Ballinasloe, and 64 in its various branches. Its entire cost was £844,216, besides £122,148 expended on docks; one-third was defrayed by parliament. The Royal Canal, incorporated by a charter of George III., in 1789, and afterwards aided by a grant of additional powers from the legislature, is navigable from Dublin to Longford and Tarmonbarry, near the head of the navigable course of the Shannon, an extent of 92 miles: its construction cost £776,213, which was wholly defrayed at the public expense. The roads and bridges in the county are for the most part in excellent order, being frequently repaired at great expense. The Circular Road is a turnpike, nearly encompassing the metropolis, and beyond which the Grand and Royal Canals for a considerable distance run nearly parallel; the former on the south, and the latter on the north, side of the city: from this road the great mail-coach roads branch in every direction, and all, excepting the south-east road through Wicklow to Wexford, are turnpikes.

Of the ancient round towers which form so remarkable feature in the antiquities of Ireland, this county contains three, situated respectively at Lusk, Swords, and Clondalkin. There is a very fine cromlech at Glen Druid, near Cabinteely, and others may be seen at Killiney, Howth, Mount Venus (in the parish of Cruagh), Glen Southwell or the Little Dargle, and Larch bill, which last is within a circle of stones; there are also numerous raths or moats. The number of religious houses existing at various periods prior to the Reformation was 24; remains exist only of those of Larkfield and Monkstown, but there are several remains of ancient churches. Although always forming the centre of the English power in Ireland, the unsettled state of society caused the surface of the county, at an early period, to be studded with castles, the remains of which are still numerous; these, with the ancient castles yet inhabited, and the principal gentlemen’s seats, are noticed in their respective parishes. Among the minor natural curiosities are some chalybeate springs, of which the best known are, one at Golden-Bridge, one in the Phoenix Park, and one at Lucan. Southwell’s Glen, about four miles south of the metropolis, is worthy of notice as a remarkably deep vale, lined with lofty trees, and adorned by a waterfall. From the district of Fingall, which was the ancient name of a large tract of indefinite extent to the north of Dublin, the distinguished family of Plunkett derives the titles of Earl and Baron.

Leave a reply