The third Earl of Leitrim had served in the army, rising to be a colonel, before he succeeded his father in the title. He was a man by no means wholly bad and possessed qualities which might, under happier circumstances, have made him famous absolute courage and a perfectly indomitablc will. Nothing could be less like the careless, absentee landlord who has been the real curse of Ireland. He was solitary by nature, and built himself his great house of Manor Vaughan away in a dreary situation, neglecting numberless beautiful prospects in less remote parts of his estate. The occupation of his life was the care of his property, and litigation was his hobby a favourite one in Ireland. On his Leitrim- property he was once fired at from a house and immediately rushed in and arrested the offender. On his Donegal estate his life was never safe and he always travelled armed; yet he lived to make old bones. He did his property

the immense service of abolishing the old system of rundale, which less energetic landlords allowed to flourish in all its weediness. But the whole trend of modern legislation, which since the Act of 1870, aims at giving the tenant an interest in his holding, ran counter to his seigneurial ideal. No sort of opposition was allowed to stand in his way ; if one man sold tenant-right to another his method was simple, to evict both.

His violence of temper was such that he had been struck off the Magistracy as totally unfit to administer justice ; and to his tenants he was, in plain English, a tyrant. He was not an avaricious tyrant ; he did not want to extort unusually exorbitant rents ; but he insisted that every man on his estate should hold his land absolutely at his landlord’s pleasure. The very idea of a tenant having a right in improvements made at the tenant’s own cost infuriated him, and in such cases he either raised the rent immediately, or ejected the man, to establish his supremacy. Nothing could be more characteristic of his tyranny, even in beneficence, than the step he took to improve the breed of sheep and cattle. He imported bulls and rams of choice breeds from Scotland, but he simultaneously, to enforce the improvement, made away with all the existing sires. Naturally he compensated their owners, but no one likes to be done good to by compulsion. Add to this imperious and arbitrary disposition a capricious temper with violent prejudices, and it is easy to see

how horrible injustices were perpetrated. Eviction in that county meant often denial of the only means of livelihood. One family which had been turned out were starving and the clergyman of the parish went to intercede for help. “Sir,” he said, “I would not give you a blanket to cover their bones.”

And thus, in April, 1878, when the news of his death came, it brought that surprise which is always occasioned when a thing long expected happens at the very last. Lord Leitrim was seventy-three when he was killed. What the immediate cause was, and whether it was a public or private feud, no one knows; but it is said that he had eighty processes of ejectment pending when he died, and, be it remembered, there was then no question of a combination against rent. He had set out to drive from Manor Vaughan to Milford on

a hired car. With him, besides the driver, was his clerk, a youth of twenty-five, who had only just entered his service. Following was another hired car, on which was Lord Leitrim’s confidential servant ; but the horse in this car was lame, and fell about a mile behind. The second car had almost reached the first point

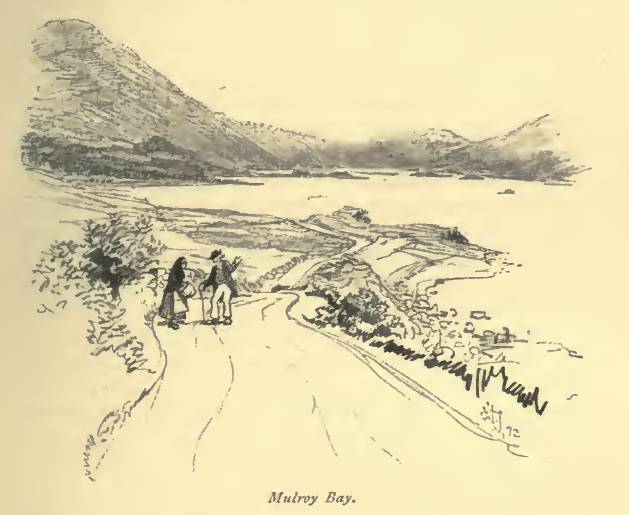

where Cratlagh wood divides the road from Mulroy, when the men on it heard two shots fired. In a moment or two they came over the brow of the hill, and saw in front of them, at some distance, the car with only Lord Leitrim on it. Then they saw him struggling with two men ; but the account is by no means clear, though it is sufficiently apparent that they made no great haste to come up. First they met the clerk running towards them, and saying he was shot; then the horse shied at a black mass in the road, and refused to pass it; it was the driver of the front car. Then they came to Lord Leitrim, lying in a pool of water, with his brains beaten out ; and, looking to the lough below, saw a boat with two men rowing away, who in

a minute were lost behind one of Mulroy’s innumerable islets. The clerk died in their hands, though the only wound on him was the scar, made by a slug, above his ear; suffusion of blood on the brain was apparently more the result of a violent shock than of the wound. The driver’s heart was riddled with

shot. Lord Leitrim had no fatal shot-wound on him ; gun butts had done the work.

The plan was boldly and cunningly laid; yet its success is surprising, for there was a patrol of two police on the road, within half a mile, who met the frightened horse galloping down to Milford by itself. The two assailants lay in wait at a point where the road comes within fifty yards of the water. The slope is covered with dense wooding down to its rocky edge, and the boat was easily hidden under it. They fired first

with charges of heavy shot ; the second time possibly with pistols. The driver was killed at the first fire, and the clerk dropped off; the car went a little further, but presumably was stopped as Lord Leitrim jumped off to struggle with the two. He was found with his teeth hard set ; he had died fighting ; and at least in this respect he died the death he merited. The boat was discovered on the far side of Mulroy, with the

oars in her ; a rough gun butt broken, a pistol, and a gun were picked up on the scene of the struggle. Why Lord Leitrim had not his revolvers that day, but left them in the second car unloaded, no one knows or rather, very likely every one in the countryside is well aware. Four men were tried for the murder on circumstantial evidence ; the torn piece of a copybook, which had been used for a wad, was fitted to a torn page in a book in one of their houses. One died in jail before the trial; the remaining three were acquitted, but died within a year or two. It is said in the countryside that the chief man in the affair is living

there yet. But one thing is certain : every Irish-speaking person within five miles of Milford, and many others, could, and would not, tell you exactly who it was that killed Lord Leitrim.

The actual scene of the murder was just beyond a black gate in the wood, about 200 yards from its northern end ; thirty or forty yards beyond that, you will notice where the whinbushes have been tracked and padded, and you will see how quick and easy a way of escape was afforded by the shelter of the wood

and the screen of the islands in the lake.

The Leitrim name has a very different repute in the county nowadays. The old Earl’s nephew and successor was then an officer in the navy. He inherited nothing that his predecessor could leave away from him; but he came down at once to the scene of the murder, and while making himself conspicuous by his attempts

to bring the criminals to justice, rode about the country unattended. The tenants, however, soon found that there was to be a new order. All the victims of arbitrary ejectment, so far as was possible, were reinstated. A very heavy outlay was made on works of drainage and reclamation.

Extract from:

Highways and byways in Donegal and Antrim (1903)

Leave a reply