Prelude to Conflict

The year 1608 marked a pivotal moment in Ireland, particularly after the influential Earls of Tyrone and Tyrconnell fled the country. This departure seemingly left the northern province vulnerable and compliant under King James I’s rule. Dr. Russell’s account, chronicled in the “Calendar of State Papers 1608-1610” at the Royal Irish Academy, outlines the government’s ambitious plans for Ulster, which included asserting the king’s sovereignty and dismantling the traditional power structures of the native lords. The aim was to establish minor freeholders who would owe allegiance directly to the Crown, thereby reducing the influence of clan heads.

Outbreak of Rebellion

Despite the apparent tranquility, the peace was abruptly disrupted. Sir Cahir O’Doherty spearheaded a rebellion by seizing Derry and rallying the clans to reclaim their lands and expel the settlers. His call, however, largely went unheeded, leading to a rapid mobilization of the king’s forces throughout the North. The royal troops, under the command of the Lord Deputy and others, effectively encircled and subdued O’Doherty’s forces. After O’Doherty’s defeat and death, the remnants of his followers, led by Shane McManus Oge O’Donnell, sought refuge on Tory Island.

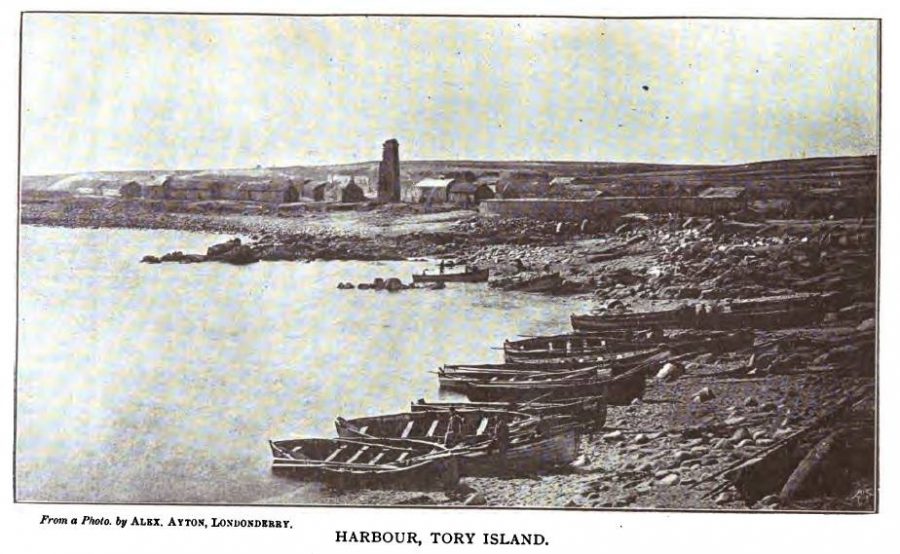

The Siege of Tory Island

On Tory Island, O’Donnell, now the de facto leader of his sept, fortified himself in a well-supplied castle. The English response was swift and brutal. Commanders Sir Henry Folliott, Sir Ralph Bingley, and Captain Gore, destroyed local boats to prevent escapes and closely monitored the coastline. They harried the woods and refuges along the shore before laying siege to the castle located on a precipitous promontory known as Tormore. The castle’s strategic position made it a formidable challenge but it was eventually surrounded.

Gruesome Negotiations and Dire Outcomes

The siege’s intensity escalated when the castle’s constable sought to negotiate with the besiegers. Facing imminent defeat, he proposed surrendering the castle and its contents. When this offer was scornfully rejected, a desperate pact was made where the constable promised the head of Shane McManus Oge O’Donnell in exchange for clemency. This ghastly requirement highlights the brutal tactics employed, which also included demands for the heads of fellow insurgents as proof of submission.

Simultaneously, a parallel but equally morbid negotiation occurred involving another garrison member, resulting in a sinister race of betrayal. Both parties, having agreed to betray each other, attempted to fulfill their grim promises, leading to further bloodshed. This competition of treachery culminated in a particularly horrific incident where, upon their return to camp, an execution was met with an immediate and deadly counterattack, illustrating the desperate and brutal nature of the siege.

Reflections on a Violent Epoch

The harrowing events on Tory Island, marked by betrayal, desperation, and slaughter, represent a somber chapter in Irish history. The account, as recounted by Dr. Russell, underscores the brutal lengths to which authority was enforced and the tragic resistance it provoked. This episode not only signifies the harsh realities of colonial conquest but also the enduring human spirit confronting overwhelming adversity. As we reflect on these events centuries later, they serve as a poignant reminder of the darker aspects of human history and the capacity for both cruelty and resilience.

Adapted from:

Scenery & Antiquities of North-West Donegal (1893)

Photos from The Lawrence Collection

Leave a reply